James Benning

Lire la suiteFirst invited to Cinéma du Réel in 2018, when his film L. Cohen earned him the Grand Prix, Benning has returned to the festival twice, presenting THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA in 2022 and Allensworth in 2023. This year, the festival wished to throw light on the entirety of his work. In the same way that the 2021 film THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA revisited the title of one of his most iconic films from the 1970s, we asked Benning to revisit his career according to one rule: each older film would have to be matched with a recent one, each film shot on celluloid with a film shot in digital. The aim of this was to allow the filmmaker to share his own experience of his work, while leaving it up to viewers to identify both changes brought on by the shift—evolutions in the rigor and in the simplicity of the set-ups—and clues tying each film back to Benning’s larger body of work.

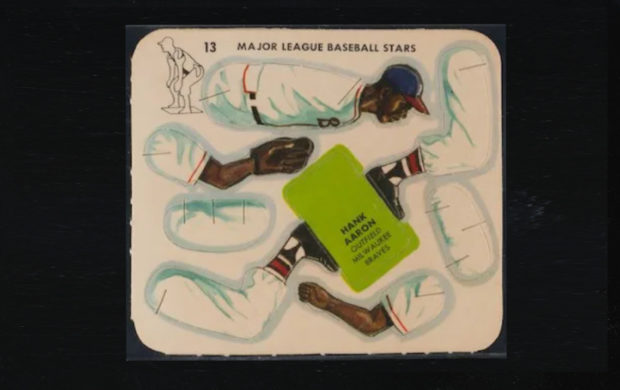

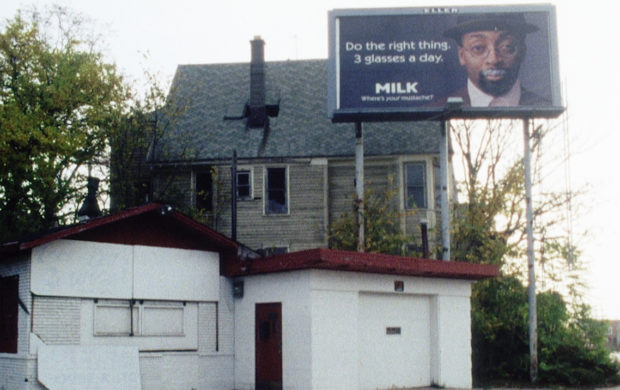

Asking James Benning to curate this programme according to a (minor) constraint was not accidental. Like the literary games of the Oulipo collective, each of his films is informed by a specific rule: 52 still shots, one for each American state, in the 2022 film THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; a series of shots filmed through the windscreen of a car travelling from New York to Los Angeles in the 1975 version. Whereas the rule, which changes each time, sets a framework, the crucial experience proposed by the filmmaker remains unaltered: an experience of time and space, requiring both patience and an ability to let oneself be overcome by images and sound, or to give in to sensation. It is an experience of landscape as action. Over time, subtle and minimal variations in events, captured by Benning’s camera, reveal the geological and political story of America contained in the landscape: its history of violence and its popular culture.

Catherine Bizern